Reflections on David Graeber’s Debt

Debt: The First 5,000 Years

Image Source - William Hogarth, A Rake's Progress, Plate 7: The Debtor's Prison

Author:

Pages:

Year :

David Graeber

400

2011

Tags:

anthropology, morality, philosophy, ancient history, finance, capitalism

“Up in our country we are human!” said the hunter. “And since we are human we help each other. We don’t like to hear anybody say thanks for that. What I get today you may get tomorrow. Up here we say that by gifts one makes slaves and by whips one makes dogs.”

Graeber sets up his argument to purposefully challenge commonly-held intuitions about debt - notably that debt is a sensible and moral obligation. In the opening pages, a woman asks him at a party, “Surely one has to pay one’s debts?” To read Debt is to not be so sure that such a premise holds water.

Graeber, who spent a couple years of his life in Madagascar, points to the former French colonies as a way to begin chipping away at the seeming solidity of debt’s underpinnings. Countries like Madagascar and notably Haiti (see sidebar) have paid hundreds of millions of dollars over past decades to their historical oppressors, the French. The dynamic is perverse, enriching the French and sanctioning a cycle of poverty in debtor countries, but it is enforced legally by the IMF and tacitly by global governments.

Diagram of a slave ship used in the Middle Passage during the Atlantic Slave Trade, dated 1789

Debt is a subversive book.

The quote above, an anthropological classic I was to learn, captures the tone emphatically. In the anecdote, a Danish hunter describes coming home from an unsuccessful hunt, only to find that other successful hunters had shared their meat with him. After thanking them, he received the unexpected response above. As Graeber summarizes, the “hunter insisted that being truly human meant refusing to make such calculations, refusing to measure or remember who had given what to whom, for the precise reason that doing so would inevitably create a world where we began … reducing each other to slaves or dogs through debt.” (79)

This anecdote, which I’ll return to later, is one of many moral and philosophical salvos that Graeber lobs towards his readers. The result is both delightful and a little uncomfortable; a reminder that to be human is to measure the worth of a person far beyond what a system of tallies (even a complex one) could ever capture; but also a suggestion that the modern financial system we’ve built, dependent on debtors and creditors, is at least in some significant ways anomalous to the human condition. Can it survive?

What about the debts you owe your parents, who at worst brought you into this world and enabled your experience of consciousness and at best nourished you, educated you, and provided for you to live a life of contentment? How much do you owe them and how long would it take to pay it all back? The question is intended to be absurd; there are some debts that can never be paid.

As recent debates over student loan forgiveness have demonstrated, the general public (at least here in the United States) is quite averse to giving anyone a “free ride”. A debt is an obligation and obligations must be paid; surely we must have learned that in college? But such expectations conflict with historical realities. Solon, pictured left, was an Athenian statesman who was one of many ancient figures famous for debt relief reforms. These reforms, often coming at times of deep societal crisis, were a way to reinvigorate the populace and unburden otherwise productive, not to mention unjustly burdened, peoples.

Your moral conceptions of debt are probably wrong.

This may appear a bold statement, if not altogether condescending and contentious, but it is apt because it reflects the reality that debt is inherently anthropological and conceptually multi-cultural. What makes the book Debt so effective is that it weaves together these many cultures, religions, and histories to make a comprehensive argument about how debt actually functions in our society, and why.

Take the partygoer mentioned earlier, “Surely one has to pay one’s debts?” Graeber keenly notes that such a sentiment is not economic in nature, but moral. But whose morality? The notion of debt has not been treated equally in all societies at all times, and the seeming common sense of having a moral duty to pay one’s debts actually has strong connections to Christianity, familiar to most Westerners. But as we’ve already seen, the Inuit hunter balks at such a sentiment.

Scenes from the Occupy Wall Street movement, where protestors call out the excesses and hypocrisies of the Great Recession era

It’s necessary and instructive to lay Graeber’s cards out on the table. He is inherently skeptical of capitalism, having been a key supporting member of the Occupy Wall Street in 2011. Graeber is motivated to subvert his readers’ expectations because he believes strongly that the systems of debt around us are on ethically fragile foundations. Much of this belief stems from one of the core takeaways of the book - the lasting and horrific connection between debt and violence. His discussion of the Atlantic Slave Trade works to crystallize the connection. To quote from the book (emphasis mine):

“The Atlantic Slave Trade as a whole was a gigantic network of credit arrangements. Ship-owners based in Liverpool or Bristol would acquire goods on easy credit terms from local wholesalers, expecting to make good by selling slaves (also on credit) to planters in the Antilles and America, with commission agents in the city of London ultimately financing the affair through the profits of the sugar and tobacco trade. Ship-owners would then transport their wares to African ports like Old Calabar.

…

By the height of the trade, British ships were bringing in large quantities of cloth (both products of the newly created Manchester mills and calicoes from India) and iron and copper ware, along with incidental goods like beads, and also, for obvious reasons, substantial numbers of firearms. The goods were then advanced to African merchants, again on credit, who assigned them to their own agents to move upstream.” (150 to 151)

Within the context of this clearly intricate system, “pawns” served as a type of debt security, with indebted merchants in Africa parlaying local rivals, unfortunate strangers, and even family members as collateral for their debt. On plantations in South America, the Caribbean and the United States, slaves were “plucked from their family, kin, friends, and community, stripped of their name, identity, and dignity … and most were simply worked to death”. (155)

I’ve stayed with this example of the Atlantic Slave Trade for a few reasons. Firstly, it is informative in understanding how the slave trade actually worked, exposing the significant financial machinery that enabled it to survive. Secondly, and building upon this first point, it helps to illustrate Graeber’s earlier argument that debt is impossible without violence. To lay it out explicitly, Graeber contends that our modern system of debt is possible only through the threat of violence, different in type than that during previous centuries of slavery, but not different in kind.

“Any system that reduces the world to numbers can only be held in place by weapons, whether these are swords and clubs, or nowadays, “smart bombs” from unmanned drones.” (386 to 387)

In a subversive book filled with challenges to the societal and financial status quo, this is the most unsettling. A hopeful reader may comfort themselves in knowing that the slave trade has largely been resigned to the history books, but what of the nature of debt? Is the distance between then and now truly as far as it seems?

Graeber’s answer is resolute. For him, slavery, even if curtailed in the modern age, “has shaped our basic assumptions and institutions in ways that we are no longer aware of and whose influence we would probably never wish to acknowledge if we were. If we have become a debt society, it is because the legacy of war, conquest and slavery has never completely gone away. It’s still there, lodged in our most intimate conceptions of honor, property, even freedom. It’s just that we can no longer see that it’s there.” (163 to 164)

As you should be able to tell by now, Debt is highly provocative, but its logic is not infallible.

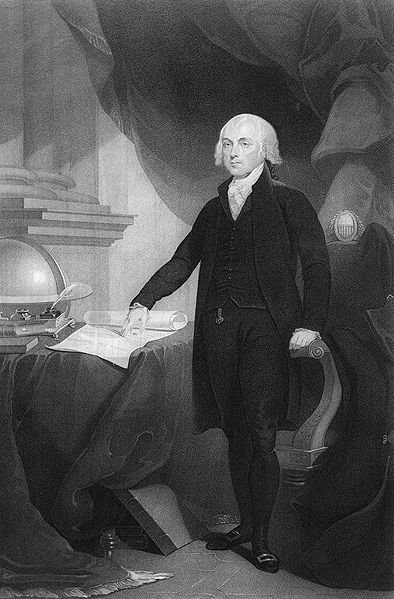

James Madison recognized that human traits such as ambition could not be ameliorated, but rather must be tamed and leveraged

I think Graeber’s arguments that wide-spread and historical violence underpin our modern financial machinery are indisputable. The historical record is simply too strong. The vast majority of American foreign policy over the last two and half centuries, for example, was consistently informed by commercial arrangements that would favor the United States. For a country that loves “free” markets, much American wealth was gained through banal exploitation and violence against less well-off peoples.

However, in highlighting violence as the means that tries to justify the ends, the great moral failing of the modern financial system, it is worth asking whether Graeber risks weakening his argument by appealing to morality?

Allow me a quick aside. I’ve recently been reading about the Greek and Roman roots in the education of the founding fathers and how those influences would themselves influence America’s early government (more on that in a future book reflection). It strikes me that much of what troubled the leading minds of the early colonies is along similar lines to Graeber’s critique – in short that a society must embrace a sense of “virtue” and “honor” in the conduct and character of its people in order to thrive.

Men like George Washington and John Adams felt deeply that the new country should be led by these men of virtue, in the Roman sense, and that political parties, a form of faction, where detrimental to the health of society because they encouraged self-interest and ambition to overrule the “good of the nation”. On the other side, those like Thomas Jefferson and James Madison took what they felt was a more pragmatic approach, recognizing that traits like ambition were impossible to stamp out entirely in favor of virtue. The lesson was clear – rather than promote a virtuous society alone, build a system where no individual’s singular ambitions can trump the system as a whole. This is the brilliance built into the checks and balances of The Constitution.

To draw the analogy more clearly, I think Graeber may be conceptualizing violence in much the same ways that Washington and Adams thought of self-interest and unchecked ambition. These are sordid traits, detrimental to humankind. But this critique misses that these traits, ambition, self-interest, and a propensity for violence, are fundamentally human. In other words, Graeber’s critique is moralistic, but it is not realistic.

Graeber is absolutely right in exposing the violent underpinnings of debt, but human beings will not stop resorting to violence when it is in their interest. To criticize the modern conception to debt as Graeber does is to critique the violent nature of the species. Rather, the key question is how do we encourage human beings to be less violent? Has the modern financial system achieved that? Or is it a mere continuation of the violence it was built on?

The dehumanizing nature of anonymous transactions

Another of Graeber’s compelling critiques is how debt often necessitates needing to treat human beings as identical. Returning again to the Inuit hunter, engaging in “transactional” behavior can be argued to be a form of immoral behavior. Modern debt relies on numerous transactions where two parties may have little knowledge of each other, incentivizing problematic outcomes like usury and greed. True humanity is fostering intimate connection to those in your community and lending your contributions not because of the promise of financial gain, but because of genuine interest in the welfare of other humans.

Again, there is little to fault here morally. These conceptions are important to uphold in how we teach our children, the values we wish to hold ideally, and to practice as often as we can. But they once again fall short of our lived realities. In this case, it is worth questioning whether treating people as identical is really a bad thing?

As just stated, I think Graeber draws a clear line between the human ability to be transactional and the horrific results that can entail. “The death of one person is a tragedy, the death of millions is a statistic.” But the magic of the modern world is that great productivity has been wrought from chains of individuals who can have little to no engagement with one another. If we were forced, through principle, to have a close connection to each person we ever transacted with, our financial circle would be quite small, and our well-being inarguably diminished by lesser opportunity.

Overall, I agree with Graeber’s sentiment. It is far too easy for those who want the anonymity of their transactions to bypass the humanity of those they are affecting. Given a transactional system that favors the transaction over the person, people will often choose the former. There is an important nuance, however. Can people be made to engage with strangers from a position of good faith and humanity? Of course they can, we have innumerable examples already. The key challenge is consistency. Society must not only praise those who show kindness to others but punish those who selfishly do not. Alas, we do not yet live in this type of society, but I am not fully convinced that debt is one of the problems preventing it.

Graeber ends his tome with an appeal on behalf of the “non-industrious poor”.

“At least they aren't hurting anyone. Insofar as the time they are taking off from work is being spent with friends and family, enjoying and caring for those they love, they're probably improving the world more than we acknowledge. Maybe we should think to them as pioneers of a new economic order that would not share our current one's penchant for annihilation.” (390)

I found ending the book this way to be poignant, and an effective way to encapsulate how Graber thinks about the human experience, as interpersonal rather than transactional. Though I’ve spent some time questioning Graeber’s conclusions and their merits, I would be remiss if I didn’t say that I found this book’s moral foundations to be solid and urgent for our time. Graeber is absolutely right in pointing out how the financial machinery of our modern world is built on an ugly past, and the less we acknowledge that in the present the more we tacitly approve of the methods used to construct our present comforts.

“Starting from our baseline date of 1700, then what we see at the dawn of modern capitalism is a gigantic financial apparatus of credit and debt that operates - in practical effect - to pump more and more labor out of just about everyone with whom it comes into contact, and as a result produces an endlessly expanding volume of material goods.” (346)

I appreciated Debt in part because I found it to be an effective challenge to the status quo. The book succeeds in not being merely subversive and provocative, but in successfully positing a moral argument undermining debt based on vast swaths of human history. There is something inordinately powerful about connecting human experiences across epochs, cultures, and continents. In truth, I went into this book expecting it to have a more financial bent. I was unexpectedly surprised to be educated in anthropology, history, and philosophy. I’m tempted to thank Graeber for the experience. I wonder what the Inuit hunter would think of that?

I was largely captivated and compelled by the ideas Debt put forward. The book is nothing if not thorough, spending the first couple hundred pages laying out conceptual frameworks on Primordial Debts, the Moral Grounds of Economic Relations, and Credit vs Bullion, before engaging in a roughly chronological telling of how we got to our current debt society.

While I did find the book highly enlightening and fair-minded in its challenges, I still remain unsure about some of its conclusions.

A mirage of civility?

Graeber would argue that the apparent civility of our modern world is belied by the necessity of violence to enforce creditors’ wishes over debtors. Institutions and norms have evolved over the past few centuries such that outright violence is rarely the preferred or default solution, but it is always implicit, and the system would collapse without the inherent ability to enforce contracts, violently if necessary.