Books

Year in Review - 2025

The List

(new to me in 2025)

And my 2025 Book of the Year is…

As someone deeply passionate about US history, Richard Rhodes’ The Making of the Atomic Bomb (MOAB for short, ironically a distinct acronym itself for “Mother of all Bombs”) had been on my radar for a number of years now. As a winner of the 1987 National Book Award and 1988 Pulitzer Prize for Non-Fiction, I was intrigued by the book’s continued relevance today as the world lurches dismayingly towards another potential nuclear arms race.

Using a trove of documents unclassified in the later 20th century and hundreds of interviews with high profile people involved in the affair, Rhodes book has earned the admiration of not only historians, but also those who work on modern nuclear policy. The book is an effort to of course not just relay the history of the Manhattan Project, to go a level deeper in understanding how the people involved at all levels conceptualized the new weapon they were creating, and its implications for a new era of warfare and global politics.

At 750 pages, the book accomplishes what it sets out to do superbly.

Going into this epic, I had expected much of the conversation to focus on the political and logistical. While those themes are no doubt explored deeply, Rhodes brilliance here was to give overwhelming weight to the technical. Though not a scientist or technologist himself, Rhodes made a concerted effort to study the physics and chemistry that underpins the bomb’s conceptual underpinnings.

The end product then is a highly technical tome which spends hundreds of pages explaining science experiments, theoretical concepts, and bringing the reader back to the state of physics in the early 20th century. The context is highly merited, and although there are passages that can leave the physics'-deficient reader (like me) a little stumped, the book completely justifies its foray into the science. The science after all, is the core reason why the atomic bomb exists today. Here is a taste of Rhodes masterful writing to emphasize the point:

“Here was no Faustian bargain, as movie directors and other naifs still find it intellectually challenging to imagine. Here was no evil machinery that the noble scientists might have hidden from the politicians and the generals. To the contrary, here was a new insight into how the world works, an energetic reaction, older than the earth, that science had finally devised the instruments and arrangements to coax forth. "Make it seem inevitable," Louis Pasteur used to advise his students when they prepared to write up their discoveries. But it was. To wish that it might have been ignored or suppressed is barbarous. "Knowledge," Niels Bohr once noted, "is itself the basis for civilization." You cannot have the one without the other; the one depends upon the other. Nor can you have only benevolent knowledge; the scientific method doesn't filter for benevolence. Knowledge has consequences, not always intended, not always comfortable, not always welcome. The earth revolves around the sun, not the sun around the earth. "It is a profound and necessary truth," Robert Oppenheimer would say, "that the deep things in science are not found because they are useful; they are found because it was possible to find them.”

What I loved most about this approach is that Rhodes takes you into the mind of the scientists he profiles. There are so many examples to pull from given all the contributions that went into the bomb, but Niels Bohr is my favorite. The Danish theoretical physicist was an incredible man whose scientific prowess was matched by his compassion and humanity. Though Bohr spent much of the war in Europe away from the events at Los Alamos, his impact on the science and on the political conception of how to use the bomb was tremendous. At points MOAB reads as a series of mini-biographies, providing the reader with a nuanced perspective of the bomb’s progenitors.

The Making of the Atomic Bomb is a crucial book to read and understand in this modern moment. Though we all can understand the ferocious power and terror of nuclear weapons, Rhodes’ book clearly illustrates that the world was forever changed after the invention of the atomic bomb. Humanity had crossed into a new realm of the scientific and geopolitical. For all of the deficiencies of human judgement in the early 20th century, the book goes to great lengths to demonstrate how seriously scientists and political figures took the new reality of the atomic bomb.

Concerning is the idea that 80+ years removed from the horrific events at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the world is beginning to downplay the human, psychological, and economic costs of deploying nuclear weapons. Nuclear arms limitations are all but disappearing this year as the United States, Russia, and China raise tensions. Worse still, there are deep questions as to whether the United States is up to the intellectual challenge of making the world safer.

I came away from reading MOAB with a deep appreciation for the political stakeholders - particularly US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and US Secretary of State Henry Stimson - in how carefully the conceptualized using the bomb. The taking of Japanese life through such monstrous means was not an afterthought, not was it an unstoppable inertia simply because the bomb had been created (the original purpose was to use it on Germany after all). Rather, the weapon was understood as a means to reach a political end - ending World War II - as all weapons before had been. Even so, leaders like Stimson recognized that nuclear weapons came with a much deeper cost than anything humankind had seen before. When one of his generals suggested making Kyoto the primary target for the bomb to strike a psychological as well as military blow, Stimson recoiled; Kyoto had such deep history and cultural significance that to inflict so much damage may be a crime beyond what was necessary to win the war.

One can only hope that today’s political, scientific, and military leaders read books like this and take away the important lessons. Across rising tensions in Ukraine and Taiwan, growing tech oligopolies, and widespread geopolitical dysfunction, there’s an unsettling that history may repeat itself again. Even still, I continue to hold out hope that the lessons are there for us, if we choose to remember them.

What I’m Most Excited For in 2026…

Ancillary Justice

Ann Leckie

I received this beautiful 10th anniversary edition for Christmas and am excited to finally take a peek into this world I’ve only ever glimpsed on bookstore shelves. Indeed, Ancillary Justice seems to be a staple of the modern sci-fi book section, and I am always a sucker for a good space opera.

Lonesome Dove

Larry McMurtry

This 1985 Pulitzer Prize winner has garnered numerous fans, including among TikTok (BookTok) influencers which is where I first heard about it. Admittedly the premise of a Western sounds like it could be a little too slow for me, but so many people swear by the character development in this book and how gripping it is that if I’m not liking it, something might definitely wrong with me, not the book.

Mark Twain

Ron Chernow

This is the year I read my first Chernow. Maybe I’ll end up swerving to Hamilton, which I’m also overdue to read, but Twain was also a Christmas gift and the flavor of the season once again. I loved Conan’s interview with Ron Chernow last year, and it does absolutely feel like Twain’s perspective would be invaluable in this time of so much despair and dysfunction.

Jimmy Corrigan

Chris Ware

Talk about a book that has gone unread on my shelves for far too long - a decade I think at this point! I bought this graphic novel way back when due to its intriguing art style and unique aspect ratio (it’s a long book not a tall one). From what I’ve heard about the book, it’s an emotional journey, so I’ll have to find the right mood. But it’s long past due that I give it a read.

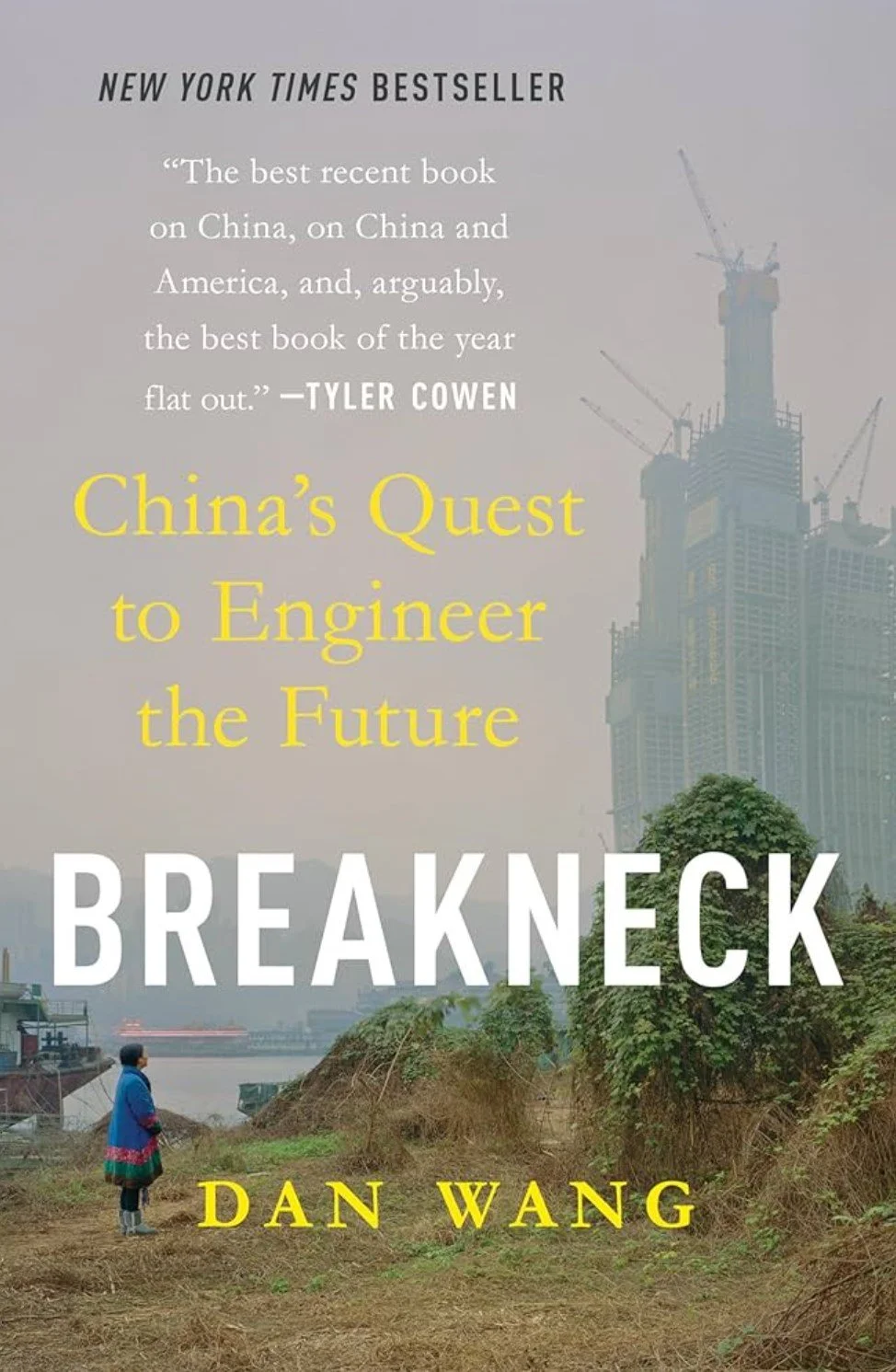

Breakneck

Dan Wang

Breakneck is the non-fiction book I am most excited to read. Why? China. As a student of International Relations, China occupies a fascinating and complex position in the world that I will likely be unraveling for the rest of my days. More meaningful, though, is the opportunity for China to represent something aspirational relative to the US’s current stagnation. Whether that’s true or not is one question I know this book can begin to unravel.